The 1979 Iran Hostage Crisis: A Defining Moment In US-Iran Relations

The 1979 Iran Hostage Situation stands as one of the most pivotal and enduring diplomatic crises in modern history, fundamentally reshaping the relationship between the United States and Iran. Beginning on a dramatic autumn day, this crisis captivated the world's attention for over a year, leaving an indelible mark on international diplomacy, American foreign policy, and the political landscape of both nations. It was a period of intense tension, failed rescue attempts, and prolonged negotiations that tested the resilience of a superpower and highlighted the complexities of a revolutionary new order in the Middle East.

The events that unfolded at the U.S. Embassy in Tehran were not merely an isolated incident but the culmination of decades of intricate geopolitical maneuvering, cultural misunderstandings, and simmering resentment. To truly grasp the gravity and long-term implications of the 1979 Iran Hostage Situation, one must delve into the historical context, the immediate triggers, and the agonizing 444 days that followed, forever altering the course of US-Iran relations and influencing global politics for generations to come.

The Seeds of Revolution: Pre-1979 Iran

To comprehend the intensity of the 1979 Iran Hostage Situation, one must first understand the volatile political climate in Iran leading up to that fateful year. For decades, Iran had been ruled by Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, a monarch who maintained close ties with the United States. The U.S. had played a significant role in restoring the Shah to power in 1953 after a coup against Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh, who had sought to nationalize Iran's oil industry. This historical intervention, coupled with the Shah's increasingly autocratic rule, his lavish spending, and his Westernization policies, fueled deep-seated resentment among many Iranians, particularly religious conservatives and the burgeoning opposition movement.

The Shah's secret police, SAVAK, brutally suppressed dissent, leading to widespread human rights abuses. While the Shah modernized parts of Iran and improved infrastructure, the economic benefits were not evenly distributed, exacerbating social inequalities. The growing discontent coalesced around Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, a prominent Shia cleric who had been exiled for his outspoken criticism of the Shah. Khomeini's message, amplified through cassette tapes and networks of mosques, resonated with a populace yearning for change, religious purity, and an end to perceived foreign domination. By late 1978, mass protests and strikes paralyzed the country, ultimately forcing the Shah to flee Iran in January 1979, paving the way for Khomeini's return and the establishment of the Islamic Republic.

November 4, 1979: The Storming of the Embassy

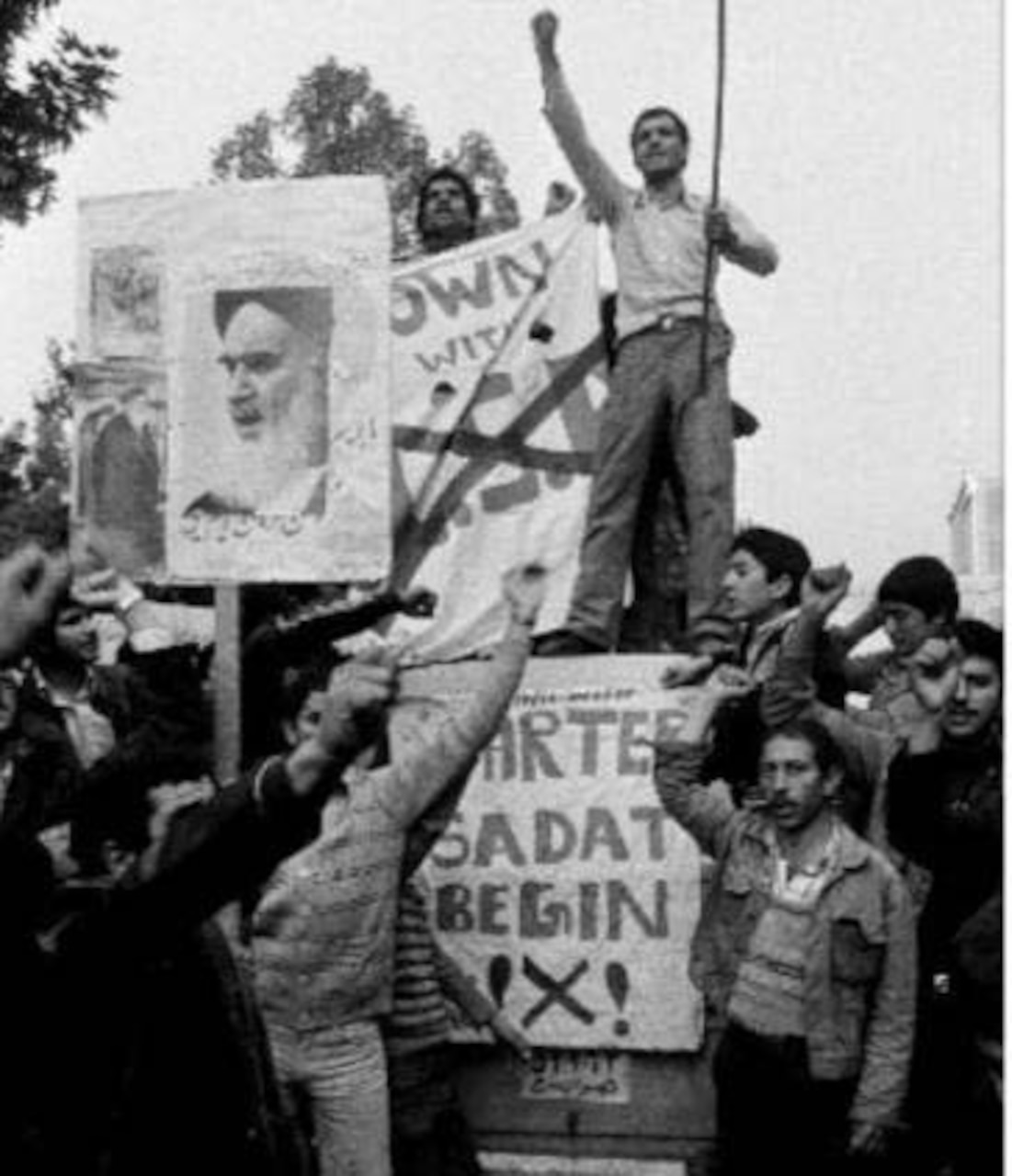

The immediate catalyst for the 1979 Iran Hostage Situation was the decision by the U.S. government to allow the ailing Shah to enter the United States for medical treatment in October 1979. This act was perceived by many Iranians, especially the revolutionary students, as a plot to reinstate the Shah and undermine the newly established Islamic Republic. The public outcry was immense, fueled by revolutionary fervor and a deep distrust of American intentions. On November 4, 1979, a group of Iranian students, calling themselves the "Muslim Student Followers of the Imam's Line," stormed the U.S. Embassy in Tehran.

The initial intent of the students was reportedly to stage a sit-in and protest the Shah's presence in the U.S., demanding his extradition to Iran to face trial. However, the situation quickly escalated beyond their initial plan. They overwhelmed the Marine guards and embassy staff, taking more than 60 American hostages. The embassy compound, once a symbol of American influence, became the epicenter of an international crisis. The students, many of whom were young and deeply committed to the revolution, viewed the embassy as a "den of spies" and a symbol of American interference in Iranian affairs. This dramatic takeover marked the official beginning of what would become known as the Iran hostage crisis (Persian: بحران گروگانگیری سفارت آمریکا).

- Will Israel Respond To Iran Attack

- War Iran Saudi Arabia

- Shah Of Iran Sopranos

- Iran Embassy Washington

- Irans President Dead

Who Were the Hostages?

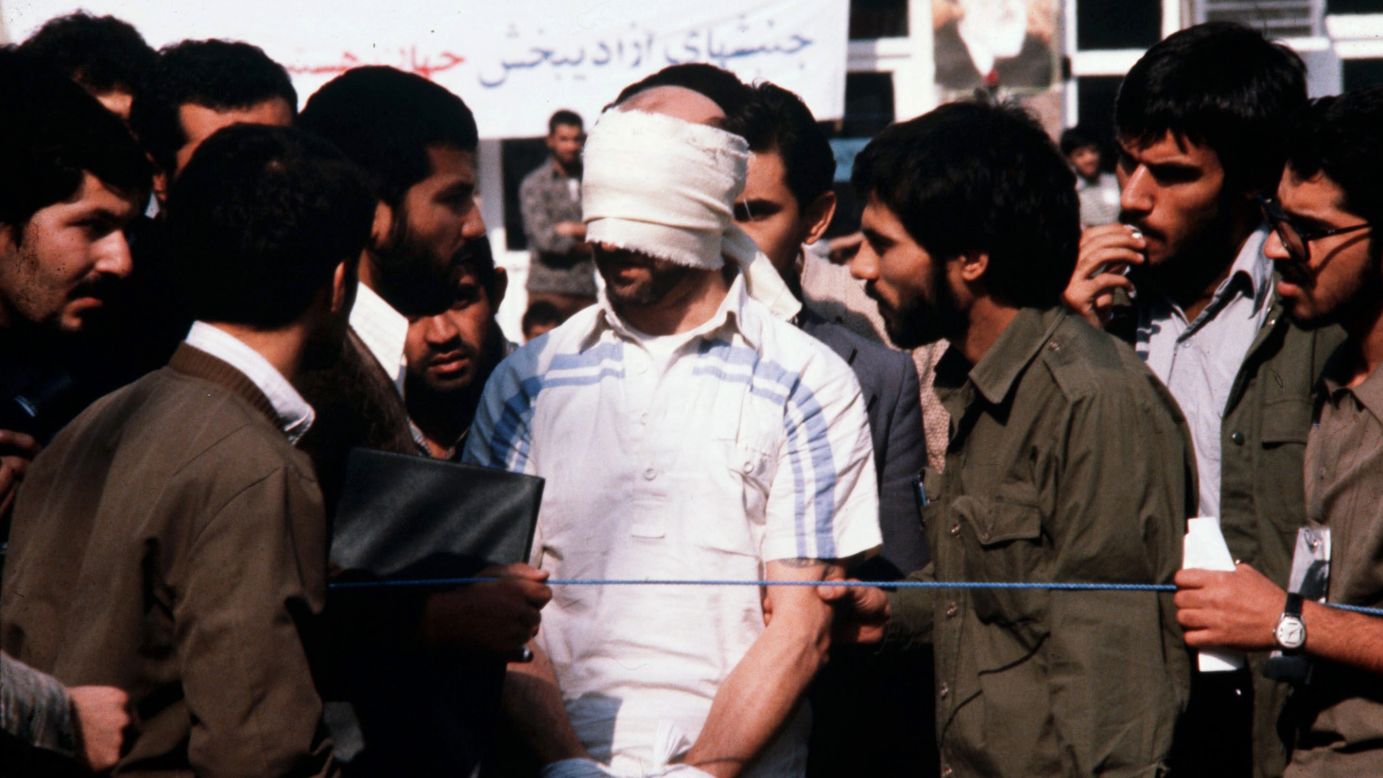

When the Iranian students seized the embassy on November 4, 1979, they detained more than 50 Americans, ranging from the chargé d’affaires to the most junior members of the staff, as hostages. The initial group of 66 Americans taken hostage included diplomats, consular officers, military personnel, and other civilian staff. Among them were individuals like Bruce Laingen, the chargé d’affaires, who was at the Iranian Foreign Ministry at the time of the takeover and was later held there. The images of American hostages, often blindfolded and surrounded by their captors, including an individual once thought incorrectly to be Mahmoud Ahmedinejad who would become Iran’s president in 2005, were broadcast globally, shocking the world and galvanizing American public opinion.

While 66 Americans were initially taken, a few were released early on, primarily women and African Americans, for what the students claimed were humanitarian reasons or to show that their grievances were not against all Americans. This left 52 hostages who would endure the full 444-day ordeal. Their captivity was a harrowing experience, marked by periods of isolation, psychological pressure, and uncertainty. The conditions varied, but the constant threat and the complete loss of freedom took a severe toll on the physical and mental well-being of the captives. The world watched, horrified, as these individuals became pawns in a high-stakes geopolitical game.

The Demands and the Stalemate

From the outset, the demands of the Iranian students and the revolutionary government were clear, albeit complex and often shifting. Their primary demand was the extradition of the Shah to Iran to face trial for alleged crimes against the Iranian people. They also called for the return of the Shah's wealth, an apology from the U.S. for its past interventions in Iran, and a guarantee of non-interference in Iran's internal affairs. For the U.S. government under President Jimmy Carter, acceding to these demands was virtually impossible. Extraditing the Shah would set a dangerous precedent and violate international norms regarding political asylum. Furthermore, the U.S. could not apologize for its historical actions without appearing to validate the revolutionary narrative and undermining its own international standing.

This fundamental disagreement led to a prolonged stalemate. The Iranian government, under the spiritual leadership of Ayatollah Khomeini, initially seemed to endorse the students' actions, viewing them as a legitimate expression of revolutionary anger. Khomeini famously declared the embassy a "den of spies" and the crisis a "second revolution." This endorsement complicated any direct negotiations, as the students often acted independently of the official government, or at least appeared to do so, making it difficult for the U.S. to identify a single, reliable negotiating partner. The crisis became a test of wills, with both sides unwilling to back down, leading to months of diplomatic deadlock and increasing frustration on the international stage.

The Global Impact and Diplomatic Efforts

The 1979 Iran Hostage Situation immediately became a global flashpoint, dominating international headlines and profoundly impacting diplomatic relations worldwide. The sight of American diplomats held captive in violation of international law (specifically the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations) sparked outrage and condemnation from numerous countries. The United Nations Security Council passed resolutions demanding the release of the hostages, and the International Court of Justice ruled that Iran had violated international law. However, these condemnations had little immediate effect on the revolutionary students or the Iranian government, who largely dismissed them as Western-biased.

President Carter's administration employed a multi-pronged approach to resolve the crisis. Diplomatic efforts included sending emissaries, engaging third-party mediators (such as the United Nations Secretary-General Kurt Waldheim and Algerian diplomats), and imposing economic sanctions on Iran. The U.S. froze Iranian assets in American banks, imposed an oil embargo, and severed diplomatic ties. These measures aimed to pressure Iran economically and politically without resorting to military force, which was seen as a last resort due to the potential for further escalation and harm to the hostages. However, each diplomatic overture seemed to hit a wall, as the revolutionary fervor in Iran remained high, and the students continued to hold firm to their demands, prolonging the agony for the hostages and their families.

Operation Eagle Claw: A Failed Rescue

As diplomatic efforts repeatedly failed to secure the release of the hostages, President Carter grew increasingly desperate. The prolonged captivity of the Americans became a symbol of American weakness and impotence on the world stage, severely impacting public morale and Carter's approval ratings. Under immense pressure, Carter authorized a daring, covert military rescue operation known as Operation Eagle Claw. The mission, launched on April 24, 1980, aimed to infiltrate Iran with Delta Force commandos, rescue the hostages from the embassy compound, and extract them from the country.

The operation was fraught with risks and complex logistical challenges. It involved multiple stages, including a desert rendezvous point (codenamed "Desert One") for helicopters and transport planes. However, the mission was plagued by mechanical failures, severe sandstorms, and poor visibility. Three of the eight helicopters experienced malfunctions, rendering the mission impossible to complete as planned. With insufficient aircraft to transport the rescue team and the hostages, the mission commander, Colonel Charles Beckwith, recommended abortion. As the forces prepared to withdraw from Desert One, a tragic collision occurred between a helicopter and a C-130 transport plane, resulting in a fiery explosion that killed eight American servicemen and injured several others. This catastrophic failure was a devastating blow to the Carter administration and a profound embarrassment for the United States.

The Aftermath of the Desert One Disaster

The failure of Operation Eagle Claw sent shockwaves through the U.S. military and political establishment. The public revelation of the aborted mission and the loss of American lives deepened the sense of national humiliation and intensified criticism of President Carter's handling of the crisis. The images of the charred wreckage at Desert One were widely circulated, further emboldening the Iranian revolutionaries and seemingly justifying their defiance. For the hostages themselves, the failed rescue attempt led to increased security measures and their dispersal to different locations across Tehran, making any future rescue attempts even more difficult.

Internally, the disaster prompted a thorough review of U.S. special operations capabilities, leading to significant reforms and the eventual establishment of the U.S. Special Operations Command (SOCOM) in 1987. It highlighted critical deficiencies in inter-service coordination, equipment reliability, and operational planning for complex, high-risk missions. While a tactical failure, the lessons learned from Desert One ultimately contributed to the development of a more robust and integrated special operations force for the United States, shaping future military interventions and counter-terrorism strategies for decades to come. The human cost, however, was immeasurable, adding another layer of tragedy to the already dire 1979 Iran Hostage Situation.

The Role of the 1980 US Election

The 1979 Iran Hostage Situation cast a long shadow over the 1980 U.S. presidential election, becoming a dominant issue that profoundly impacted President Jimmy Carter's re-election campaign. The inability to secure the hostages' release despite numerous efforts was widely perceived as a sign of weakness and indecisiveness by the Carter administration. Public opinion polls consistently showed that Americans were deeply concerned about the crisis, and many felt that the nation's prestige had been severely damaged. This sentiment played directly into the hands of Carter's Republican challenger, Ronald Reagan.

Reagan skillfully capitalized on the public's frustration, portraying Carter as ineffective and promising a stronger, more decisive foreign policy. His campaign rhetoric often highlighted the perceived humiliation of the U.S. on the world stage, implicitly linking it to the ongoing hostage crisis. While Carter dedicated much of his time and energy to resolving the crisis, even canceling campaign events to focus on negotiations, this commitment paradoxically reinforced the image of a president consumed by an intractable problem. The crisis became a symbol of national malaise, and the public's desire for a fresh start and a return to American strength ultimately favored Reagan, who promised "peace through strength."

Carter's Dilemma and Reagan's Rise

President Carter found himself in an impossible dilemma. Any perceived concession to Iran could be seen as weakness, while a failure to secure the hostages' release further eroded his political capital. He walked a tightrope, trying to balance diplomatic engagement with maintaining national dignity. This constant struggle, exacerbated by the failed rescue attempt, made it incredibly difficult for him to shift public attention to other policy achievements or economic improvements. The 1980 election table of contents on November 4, 1979, a group of Iranian students stormed the U.S. Embassy in Tehran, taking more than 60 American hostages, forever intertwining the crisis with the electoral cycle.

As the election drew closer, speculation mounted that Iran might intentionally delay the hostages' release to influence the election outcome, though concrete evidence of this remains debated. Regardless, the perception that the crisis was tied to the election was pervasive. Ronald Reagan's landslide victory on November 4, 1980, exactly one year after the embassy takeover, was widely interpreted as a public mandate for a new approach to foreign policy and a clear rejection of the status quo that the hostage crisis had come to represent. The shadow of the 1979 Iran Hostage Situation loomed large, effectively sealing Carter's political fate and ushering in a new era of American conservatism and assertiveness on the global stage.

The Algiers Accords and Release

Despite his electoral defeat, President Carter remained committed to securing the release of the hostages before leaving office. Negotiations intensified in the final months of 1980, primarily mediated by Algeria. The Iranians, facing mounting international pressure and the potential for a more aggressive stance from the incoming Reagan administration, finally began to show a willingness to negotiate seriously. The protracted negotiations culminated in the Algiers Accords, signed on January 19, 1981, just hours before Ronald Reagan's inauguration.

The agreement outlined the terms for the hostages' release, which included the unfreezing of Iranian assets in the U.S., a pledge by the U.S. not to interfere in Iran's internal affairs, and the establishment of an Iran-U.S. Claims Tribunal at The Hague to resolve financial disputes between the two countries. Crucially, the U.S. did not explicitly apologize for its past actions, nor did it extradite the Shah (who had died in Egypt in July 1980). The Iranians held the American diplomats hostage for 444 days. On January 20, 1981, minutes after Reagan was sworn in, the 52 remaining American hostages were finally released and flown out of Tehran, ending one of the most agonizing diplomatic standoffs in history.

The Long-Term Legacy of the Crisis

The release of the hostages brought immense relief to the United States, but the scars of the 1979 Iran Hostage Situation ran deep. The crisis fundamentally altered U.S. foreign policy, leading to a more cautious approach to engaging with revolutionary regimes and a greater emphasis on counter-terrorism and special operations capabilities. It also solidified a deep-seated animosity between the U.S. and Iran that persists to this day. The image of the U.S. Embassy in Tehran on November 4, 1979 (cnn.com) became an iconic symbol of revolutionary defiance and American vulnerability.

For Iran, the crisis was a moment of national unity and revolutionary triumph, cementing the legitimacy of the new Islamic Republic and Ayatollah Khomeini's leadership. It demonstrated Iran's willingness to defy a superpower and assert its independence. However, it also led to Iran's international isolation and economic hardship. The crisis laid the groundwork for decades of mistrust, proxy conflicts, and a complex, often hostile, relationship between the two nations, influencing everything from nuclear proliferation debates to regional stability in the Middle East. The 444 days the Americans were held hostage at the embassy in Tehran continue to resonate, shaping perceptions and policies on both sides.

Lessons Learned: Diplomacy, Power, and Perception

The 1979 Iran Hostage Situation offers invaluable lessons in international relations, the dynamics of revolutionary movements, and the challenges of crisis management. Firstly, it underscored the profound impact of historical grievances and cultural misunderstandings on diplomatic relations. The students' actions, while unlawful, stemmed from a deep-seated resentment against perceived American imperialism and support for an oppressive regime. This highlights the importance of understanding the historical context and popular sentiment in foreign policy decisions.

Secondly, the crisis demonstrated the limitations of conventional power in dealing with non-state actors or ideologically driven movements. Despite its military and economic might, the U.S. found itself largely impotent in the face of a determined group of students supported by a revolutionary government. This forced a re-evaluation of diplomatic strategies and the role of covert operations. Finally, the crisis vividly illustrated the power of perception and the media in shaping public opinion and influencing political outcomes. The constant media coverage, often featuring images of the hostages, created immense pressure on the U.S. government and played a significant role in the 1980 presidential election. The 1979 Iran Hostage Situation remains a stark reminder of the complexities and unforeseen consequences that can arise when revolutionary fervor clashes with established international norms.

In conclusion, the 1979 Iran Hostage Situation was more than just a diplomatic incident; it was a watershed moment that forever altered the geopolitical landscape. Its 444-day duration, from the storming of the U.S. Embassy in Tehran on November 4, 1979, to the release of the 52 hostages on January 20, 1981, symbolized a dramatic shift in power dynamics and the emergence of a new, assertive Iran. The crisis continues to be a crucial reference point for understanding the deep-rooted animosity between the United States and the Islamic Republic of Iran, influencing foreign policy debates and regional conflicts even today.

What are your thoughts on the long-term impact of the 1979 Iran Hostage Situation on global politics? Share your insights in the comments below! If you found this article insightful, consider sharing it with others who might be interested in this critical piece of history, and explore our other historical analyses on international relations.

1979 Iran hostage crisis | CNN

Iran Hostage Crisis Fast Facts | CNN

40 Years After Hostage Crisis, Iran Remains Hotbed of Terrorism > U.S